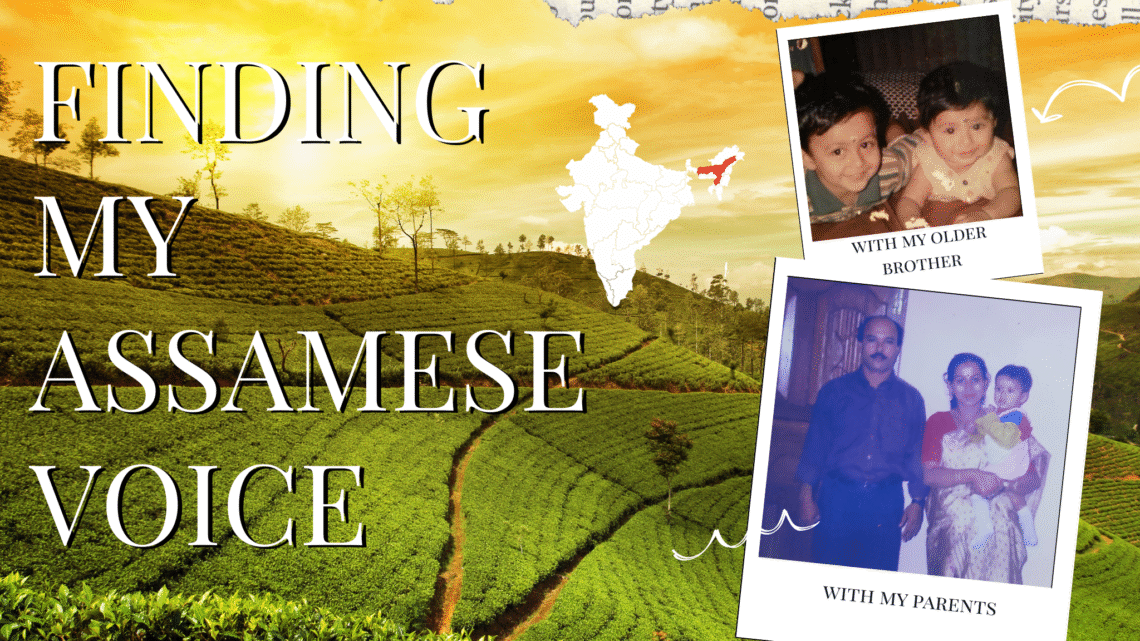

Finding My Assamese Voice

The most common question I get, even after I say I’m Assamese, is: “Oh, so you’re Bengali?”

I smile politely. But inside, something flickers. It’s not anger, just a quiet ache that comes from being misunderstood, again.

I was born in Assam, in a small town where the air smelled like mustard oil and rain, where every season had a rhythm, and the Bihu dhol echoed through courtyards like a heartbeat. But I didn’t grow up there. My father, who worked for ONGC, was posted across South India, so my childhood unfolded under the hot, coastal skies of Tamil Nadu.

Assam became a memory I carried like an heirloom, carefully, even if I didn’t fully know how to wear it.

We celebrated Bihu in Tamil Nadu with the Assamese Association. My mother would make pitha and my father would play Zubeen Garg or Khagen Mahanta, sometimes even sing along. There was dhol, pepa, friends to join the husori. That was our Assam, tucked gently inside a Tamil-speaking neighbourhood.

Over time, though, I felt myself drifting. I sometimes struggled to remember certain Assamese words. The songs became harder to sing. A strange kind of guilt settled in, the kind only diasporic children know. I started wondering if I had the right to claim a place that was slipping from my vocabulary.

And then my parents moved back to Assam after retirement.

That first trip home felt like a reunion with something more than land, it was a reunion with a rhythm I had forgotten I knew. The sounds, the smells, the dialects—they didn’t feel foreign. They felt like stories my bones remembered even when my mouth did not.

I began to listen more, to the way my aiita(maternal grandmother) hummed lullabies from memory, to the cadence of folk songs sung during evening chores. I sat through puja recitals with closed eyes, feeling the centuries of devotion tucked into every syllable. I watched young Bihu dancers not as a distant observer, but as someone returning to a forgotten festival inside myself.

This wasn’t nostalgia. It was recognition.

I realized that being Assamese wasn’t about how fluent my accent was, or how often I wore traditional attire. It was about memory. It was about intent. It was about returning, again and again, to something that was always mine, even in absence.

I don’t have all the answers. I still rely on my parents to explain cultural nuances I didn’t grow up with. But I no longer feel like a guest in my own identity.

Assam, to me, is not just where I was born. It’s the music that lives in the pauses of conversation, the scent of black tea boiling with tulsi, the feeling of earth between your toes when you step into a paddy field. It’s the silence that follows after the dhol stops and your heart is still dancing.

This journey of remembering, reclaiming, and reconnecting is mine. Quiet, personal, and incomplete in all the right ways.

And in that incompleteness, I have found something whole.

Till the next time,

Akash.